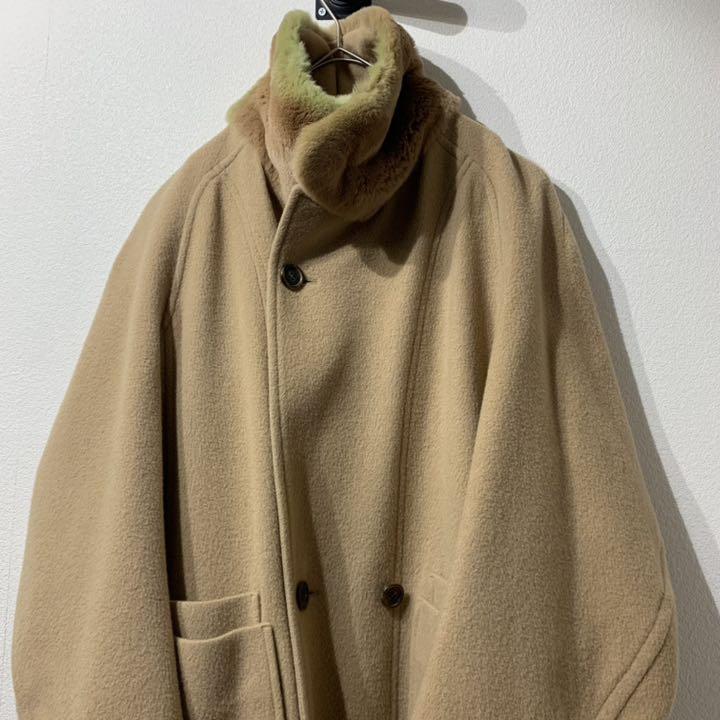

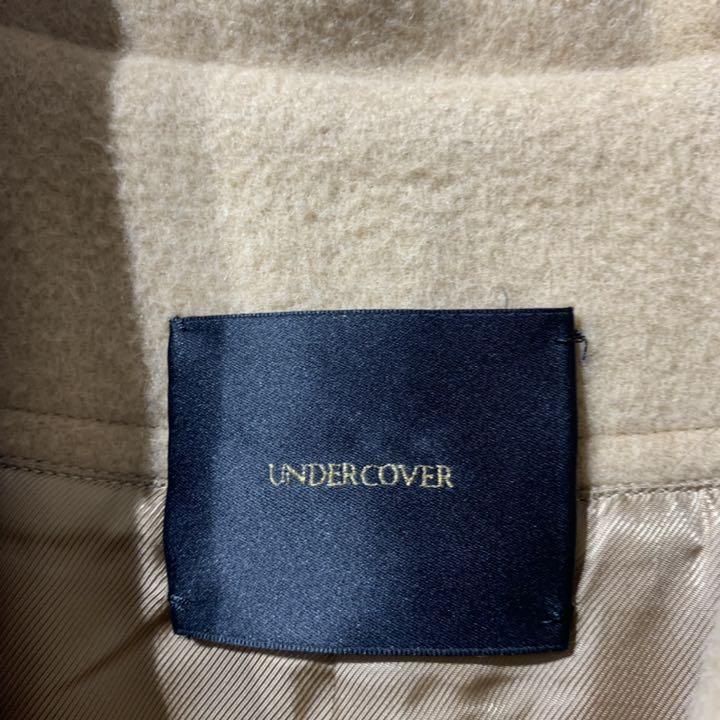

希少 14aw UNDER COVER 衿ファーラグランダブルコート ベージュ

(税込) 送料込み

商品の説明

ご覧頂きありがとうございます > _ >

ファーがとてもかわいいです。

アンダーカバーらしいデザインとなっており、ルックにも掲載されております。

希少価値高い商品となっております。

色々なシーンで着用でき、シルエットも良いです > _ >

購入場所 アンダーカバー 金沢店

ファーを若干変色させました。それも含めてデザインとなっております。質感は変わりません。

その他特に大きな目立つ傷や汚れはございません!

これからもたくさん着用して頂けます > _ >

これからの季節にはピッタリなアイテムだと思います!

サイズ 2

着丈86 身幅58 肩幅40 袖丈64

他にも沢山のジャンルの服を出品しております!

他商品とのおまとめ購入大歓迎です♬

コメント頂きましたらおまとめさせて頂きますのでお気軽にどうぞ > - >

よろしくお願いしますm(_ _)m商品の情報

| カテゴリー | レディース > ジャケット/アウター > ロングコート |

|---|---|

| 商品のサイズ | M |

| ブランド | アンダーカバー |

| 商品の状態 | 目立った傷や汚れなし |

希少 14aw UNDER COVER 衿ファーラグランダブルコート ベージュ-

希少 14aw UNDER COVER 衿ファーラグランダブルコート ベージュ

希少 14aw UNDER COVER 衿ファーラグランダブルコート ベージュ

希少 14aw UNDER COVER 衿ファーラグランダブルコート ベージュ

希少 14aw UNDER COVER 衿ファーラグランダブルコート ベージュ

希少 14aw UNDER COVER 衿ファーラグランダブルコート ベージュ

希少 14aw UNDER COVER 衿ファーラグランダブルコート ベージュ

希少 14aw UNDER COVER 衿ファーラグランダブルコート ベージュ

希少 14aw UNDER COVER 衿ファーラグランダブルコート ベージュ

希少 14aw UNDER COVER 衿ファーラグランダブルコート ベージュ

待望☆】 【ドゥロワー】ファーコート ロングコート - brightontwp.org

希少!!】 ペギーラナ リバーウールペンシルコート ロングコート

2023年最新】アンダーカバー/ロングコートの人気アイテム - メルカリ

大人気】ムートンコート ファー 腰リボン M 本革 ベージュ系 即納

半額】 新品 未使用 REVERSIBLE BOA PONCHO COAT ロングコート

herlipto Siena River Long Coat 新品タグ付 充実の品 www.causus.be

希少!!】 ペギーラナ リバーウールペンシルコート ロングコート

定番 ヘルノHERNOエコファーコート ロングコート - elroble.apde.edu.gt

早い者勝ち カーサフライン ビッグショール ロングコート ロングコート

☆新品タグ付き☆ TATRAS LAVIANA ダウンコート ラクーンファー付き 夏

品質が tiara ティアラ バイカラー ノーカラー スプリングコート

ダウンコート ダウンジャケット ホワイト 人気提案 www.coopetarrazu.com

大人気新品 定価126万円 ミファエル 高級 ロングカーディガン 毛皮

上品 CELINE BY PHILO☆カシミヤクロンビーコート セリーヌ PHOEBE

超可爱の コラボ クリスチャンラクロワ デジグアル コート ブルー 40

超可爱の コラボ クリスチャンラクロワ デジグアル コート ブルー 40

アウターで NINE ミリタリーアウター& リリーブラウンシャツ石原さとみ

新作人気 volume standcollar Eaphi midi フリー coat ロングコート

魅力的な ジャーナルスタンダード ラックス リンネル ロングコート

![お買得】 [North Face] 日本未発売 RIMO リモ フリース 新品未使用](https://static.mercdn.net/item/detail/orig/photos/m92481688560_1.jpg)

お買得】 [North Face] 日本未発売 RIMO リモ フリース 新品未使用

てなグッズや ループブロッキング イエナ IENA ノーカラーコート

激安通販 45R インディゴギマ刺繍コート ロングコート - www.georeisen

高級感 着物リメイク/新反物銘仙/正絹/フード付きコート/コスプレ/美品

SHIPS ウールカシミアノーラペルコート 新しいスタイル 49.0%割引

再再販! JNBY アウター ロングコート - elroble.apde.edu.gt

ポイント10倍】 タグ付き新品【HERNO ヘルノ】大人もOK!パッド入り

ピオニハウスコート♡ポテチーノ♡さえら♡ヒスクローネ 正規品 51.0

高級感 着物リメイク/新反物銘仙/正絹/フード付きコート/コスプレ/美品

レビュー高評価の商品! ラグランヘチマ衿コート ニット 着物、浴衣

新作人気 volume standcollar Eaphi midi フリー coat ロングコート

商品の情報

メルカリ安心への取り組み

お金は事務局に支払われ、評価後に振り込まれます

出品者

スピード発送

この出品者は平均24時間以内に発送しています