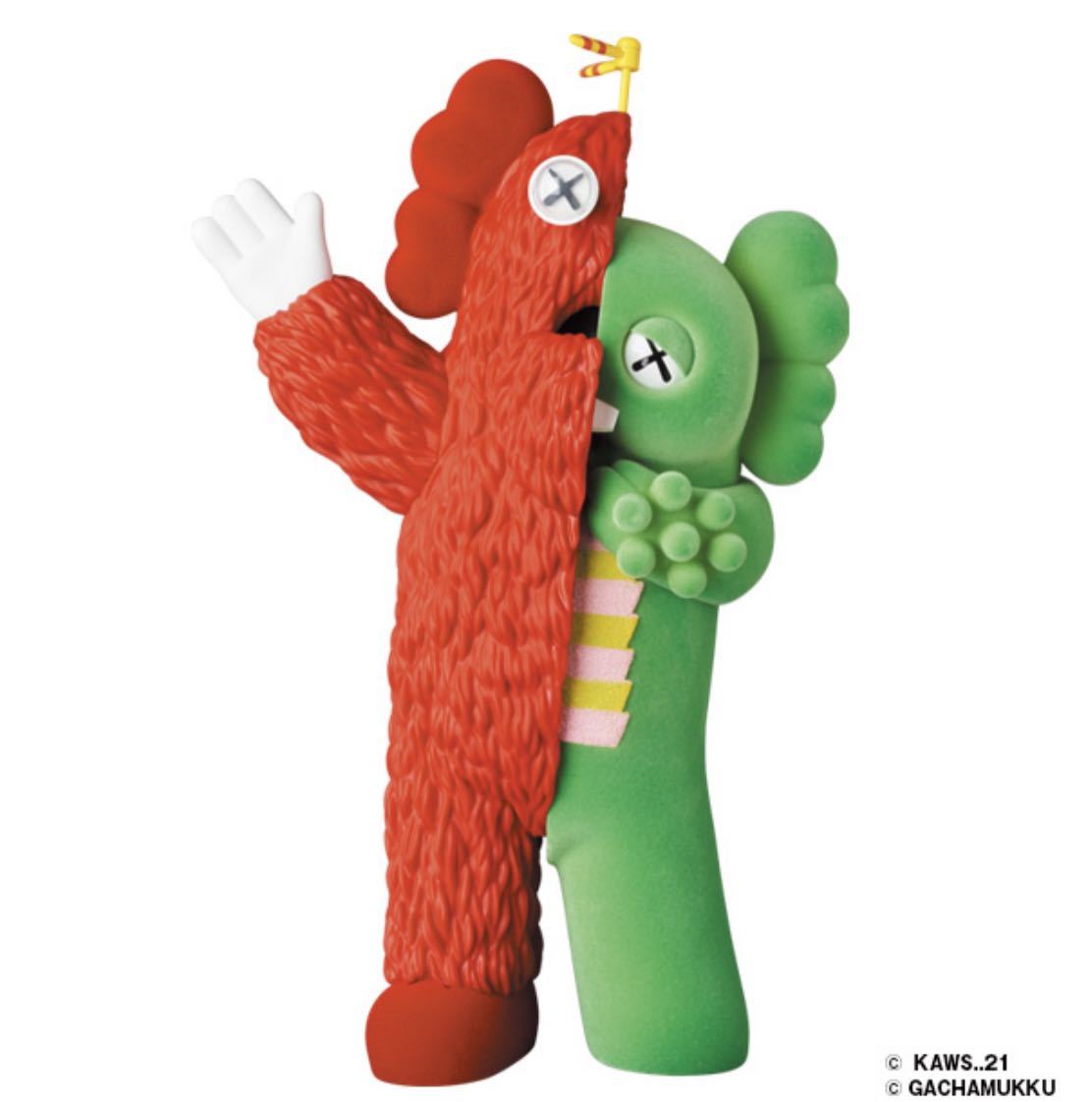

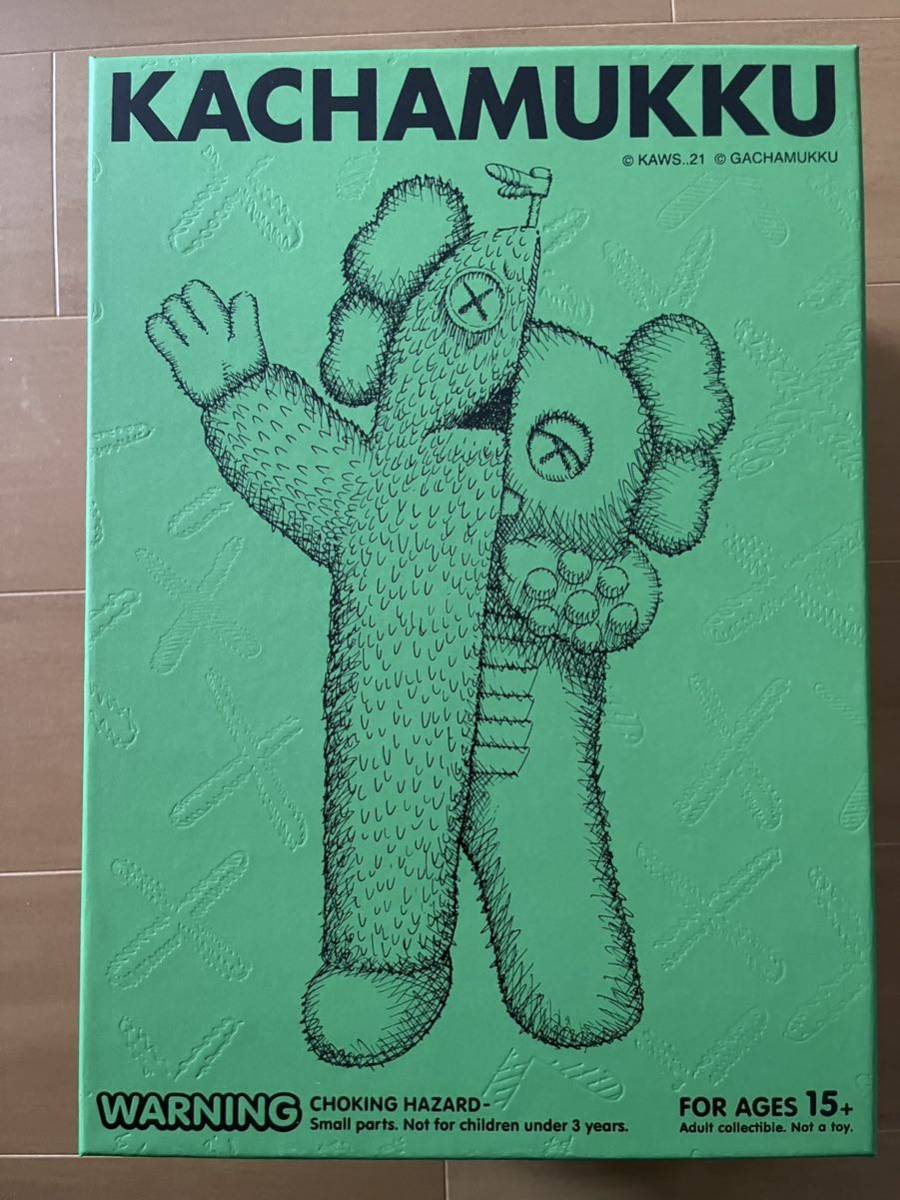

KAWS ガチャピンムック ブラック medicom toy

(税込) 送料込み

商品の説明

ご覧いただきありがとうございます。

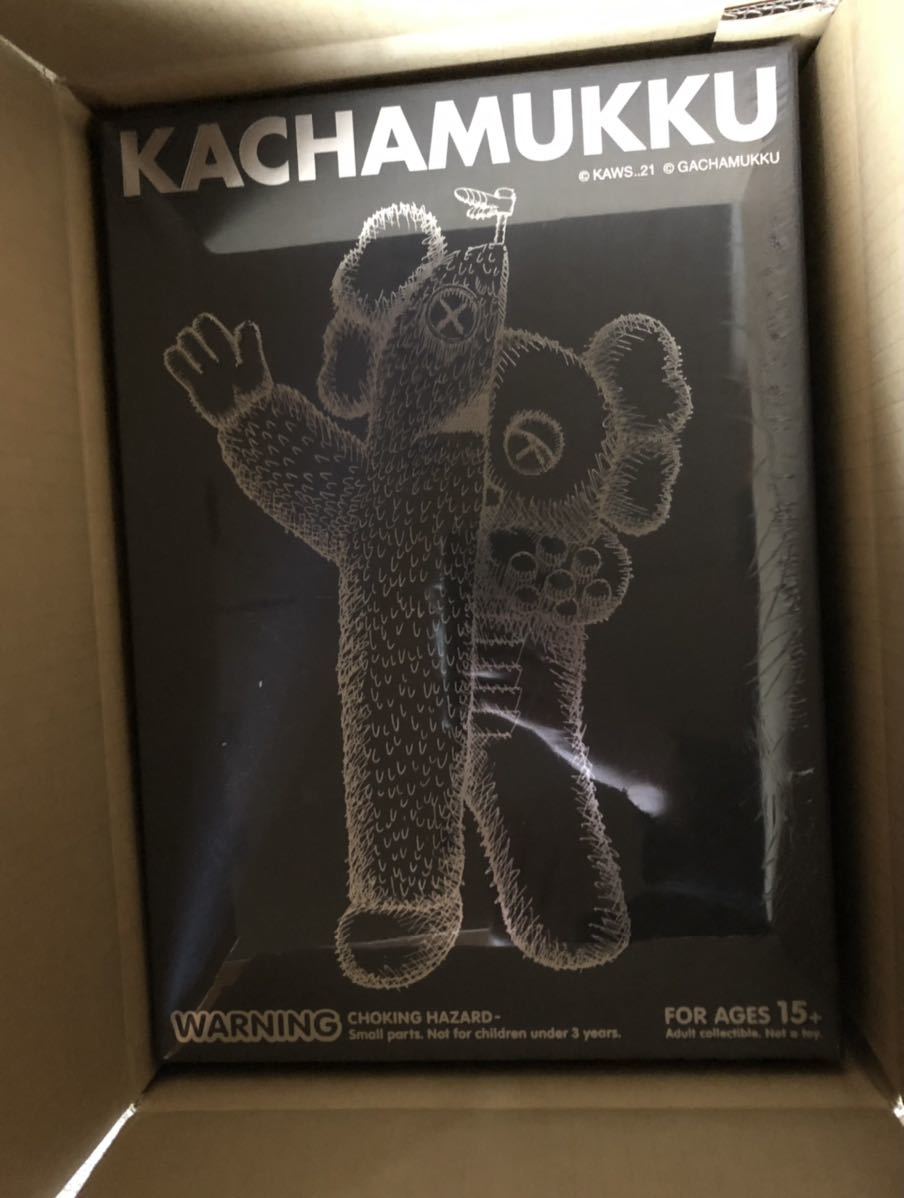

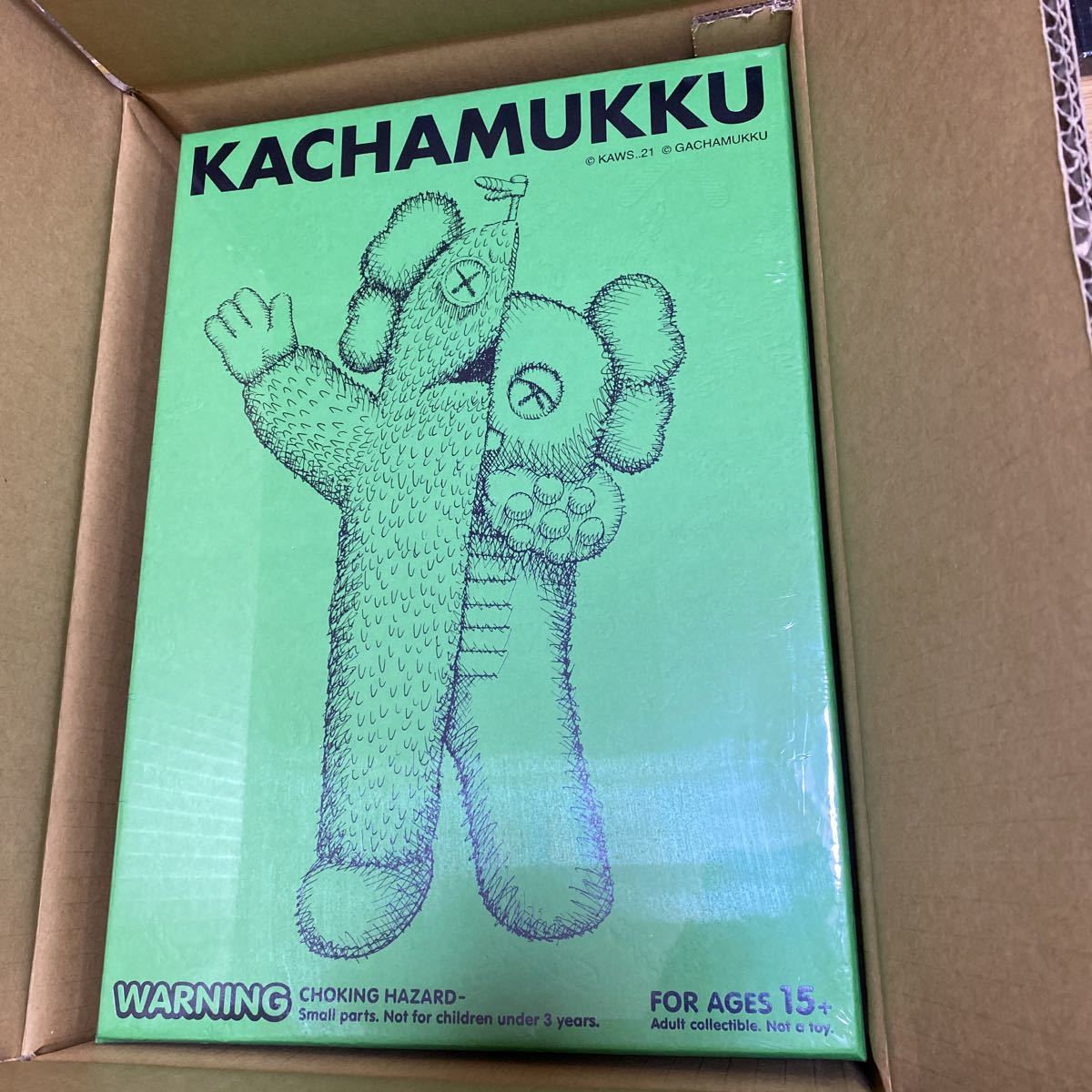

KAWS ガチャピンムック ブラックとなります。

公式オンラインで購入いたしました。

断捨離のため出品

新品未開封品

送料無料

#kaws

#ガチャピン

#ムック

#フィギュア

#カウズ商品の情報

| カテゴリー | おもちゃ・ホビー・グッズ > フィギュア > その他 |

|---|---|

| 商品の状態 | 新品、未使用 |

楽天市場】【MEDICOM TOY KAWS KACHAMUKKU ORIGINAL / BLACK

KAWS KACHAMUKKU メディコム トイ カウズ ガチャピン ムック smcint.com

KAWS ガチャピンムック ブラック medicom toy 最善 hachidori87.com

☆新品未展示 KAWS KACHAMUKKU ORIGINAL / ガチャピン ムック

楽天市場】100%本物保証 新品 カウズ KAWS x メディコム・トイ

定番のお歳暮 MEDICOM TOY - Kaws kachamukku ガチャピン ムック ベア

総合3位】 KACHAMUKKU Kaws ガチャピン ムックの通販 by ベッカム's

大人の上質 MEDICOM TOY (メディコムトイ) x KAWS KACHAMUKKU BLACK

楽天市場】100%本物保証 新品 カウズ KAWS x メディコム・トイ

楽天市場】【MEDICOM TOY KAWS KACHAMUKKU ORIGINAL / BLACK

SALE得価】 MEDICOM TOY - Kaws KACHAMUKKU ガチャピン ムックの通販

総合3位】 KACHAMUKKU Kaws ガチャピン ムックの通販 by ベッカム's

総合3位】 KACHAMUKKU Kaws ガチャピン ムックの通販 by ベッカム's

MEDICOM TOY メディコムトイ x KAWS KACHAMUKKU BLACK ×カウズ

![期間限定ポイント5倍キャンペーン中!!] 新品 カウズ KAWS x メディコム](https://makeshop-multi-images.akamaized.net/cliffedge/itemimages/000000010147_3_QVF7QTo.jpg)

期間限定ポイント5倍キャンペーン中!!] 新品 カウズ KAWS x メディコム

MEDICOM TOY - KAWS KACHAMUKKU Black ガチャピン ムック 新品未開封の

楽天市場】MEDICOM TOY(メディコムトイ) x KAWS KACHAMUKKU BLACK

MEDICOM TOY - KAWS kachamukku カウズ ガチャピン ムック

MEDICOM TOY (メディコムトイ) x KAWS KACHAMUKKU BLACK ×カウズ

楽天市場】MEDICOM TOY(メディコムトイ) x KAWS KACHAMUKKU BLACK

MEDICOM TOY (メディコムトイ) x KAWS KACHAMUKKU BLACK ×カウズ

全国無料得価 ヤフオク! - KAWS KACHAMUKKU ORIGINAL 新品未開封

ヤフオク! -「kaws ガチャピン」(キューブリック、ベアブリック

☆新品未展示 KAWS KACHAMUKKU ORIGINAL / ガチャピン ムック

ヤフオク! -「kaws ガチャピン」(キューブリック、ベアブリック

安い2023 MEDICOM TOY - KAWS KACHAMUKKU ガチャピン ムックセットの

定番人気SALE kaws ガチャピンKAWS KACHAMUKKUの通販 by ときときん's

KAWS ガチャピンムック ブラック medicom toy 最善 hachidori87.com

楽天市場】MEDICOM TOY(メディコムトイ) x KAWS KACHAMUKKU BLACK

サイズ MEDICOM ガチャピン ムック セットの通販 by キャンディー

楽天市場】MEDICOM TOY(メディコムトイ) x KAWS KACHAMUKKU BLACK

ホビー MEDICOM TOY - Gachapin and Mukku

MEDICOM TOY - KAWS kachamukku カウズ ガチャピン ムック ガチャ

KAWS ガチャピンムック ブラック medicom toy 最善 hachidori87.com

ヤフオク! -「メディコムトイ ガチャピン ムック」の落札相場・落札価格

楽天市場】MEDICOM TOY(メディコムトイ) ×KAWS KACHAMUKKU RED/GREEN

MEDICOM TOY (メディコムトイ) x KAWS KACHAMUKKU BLACK×カウズ

ヤフオク! -「メディコムトイ ガチャピン ムック」の落札相場・落札価格

ヤフオク! -「メディコムトイ ガチャピン ムック」の落札相場・落札価格

入手困難】新品 メディコム ガチャピン ムック ポンキッキーズ UDF

商品の情報

メルカリ安心への取り組み

お金は事務局に支払われ、評価後に振り込まれます

出品者

スピード発送

この出品者は平均24時間以内に発送しています