ウォーハンマー Warhammer AOS ハイエルフ

(税込) 送料込み

商品の説明

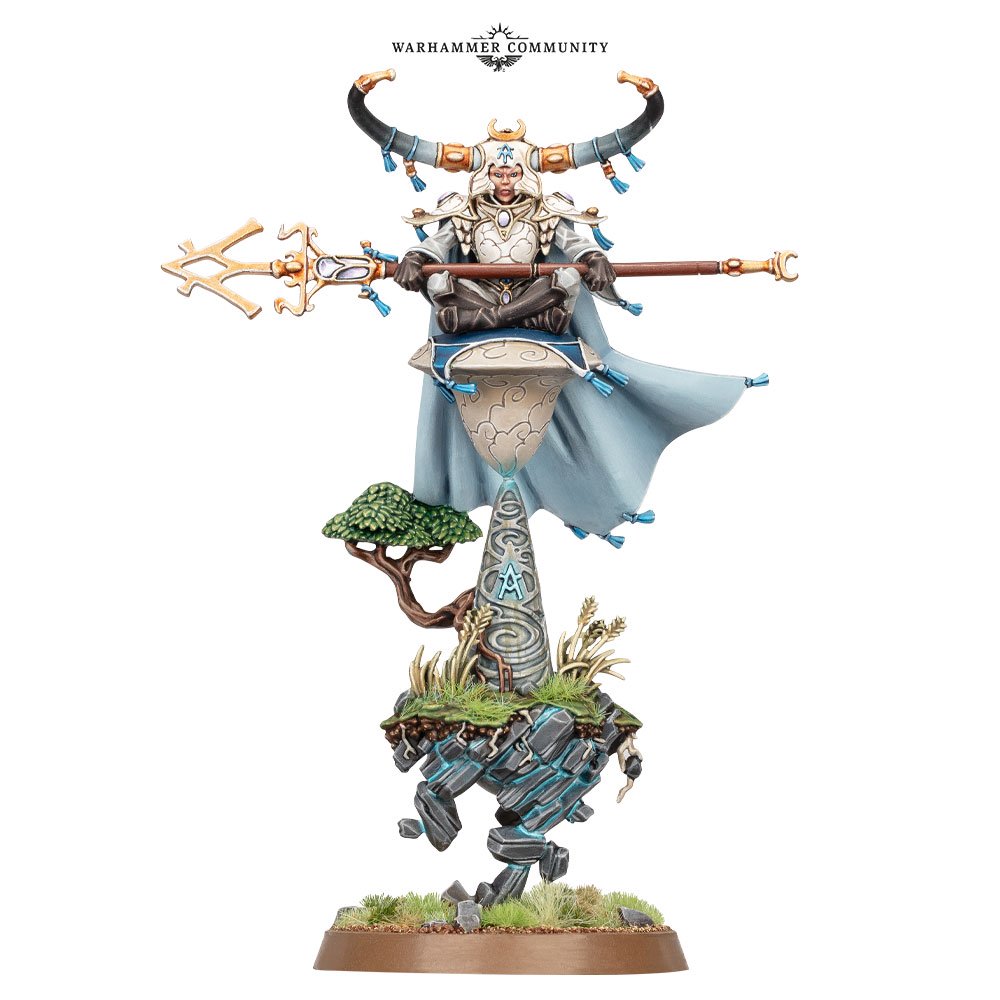

ウォーハンマー Warhammer AOS ハイエルフ

High elf lord on frost phoenix

20 phoenix Guard

five dragon princes new sealed

このアーミーは見事に塗装されています。非常に安全に発送されます。

ご質問がある場合、またはもっと写真が必要な場合はお尋ねください。絵の細部のレベルは非常に良いです。

写真をよくご覧の上、ノークレーム・ノーリターンでお願い致します。

Pro painted excellent condition

no claim no return thank you商品の情報

| カテゴリー | おもちゃ・ホビー・グッズ > フィギュア > その他 |

|---|---|

| 商品の状態 | 目立った傷や汚れなし |

ウォーハンマー Warhammer AOS ハイエルフ | www.talentchek.com

ウォーハンマー Warhammer AOS ハイエルフ - その他

ウォーハンマー Warhammer AOS ハイエルフ - その他

ウォーハンマー Warhammer AOS ハイエルフ | www.talentchek.com

ウォーハンマー Warhammer AOS ハイエルフ - その他

ウォーハンマー Warhammer AOS ハイエルフ | www.talentchek.com

ウォーハンマー Warhammer AOS ハイエルフ - その他

ウォーハンマー Warhammer AOS ハイエルフ - その他

ウォーハンマー Warhammer AOS アエルフ ルミネス テクリス

2023年最新】ウォーハンマー aosの人気アイテム - メルカリ

IP65防水 ウォーハンマー ハイエルフ アエルフ - 模型/プラモデル

ウォーハンマー Warhammer AOS ハイエルフ - その他

ウォーハンマー Warhammer AOS ハイエルフ | www.talentchek.com

ウォーハンマー Warhammer AOS ハイエルフ | gualterhelicopteros.com.br

ウォーハンマー Warhammer AOS アエルフ ルミネス テクリス

ウォーハンマー AOS ダークエルフ ドレッドロード オン ブラック

ウォーハンマー ハイエルフ ドラゴン-

2023年最新】warhammer aosの人気アイテム - メルカリ

ウォーハンマーファンタジーバトルから15年ぶりに帰ってきたらAOS

IP65防水 ウォーハンマー ハイエルフ アエルフ - 模型/プラモデル

気になったニュース】ハイエルフの方たちの続報~お馬さん~ - たるい

ウォーハンマー ハイエルフ ドラゴン-

ウォーハンマー Warhammer AOS アエルフ ルミネス テクリス

ウォーハンマー ハイエルフ ドラゴン-

ウォーハンマー ハイエルフ ロードオブドラゴン | www.crf.org.br

ウォーハンマー Warhammer AOS アエルフ ルミネス テクリス

RoR 雑文 いつかまたFB

Warhammer ウォーハンマー シェイドスパイア おまけ - 通販

ウォーハンマーのミニチュアで遊べるAge of Fantasyをやってみた

RoR 雑文 いつかまたFB

ウォーハンマードラゴン Warhammer High Elf Dragon FB | www

ウォーハンマー公式JPN on X:

感謝の声続々! ウォーハンマー 模型/プラモデル Warhammer AOS

アーミー紹介: Muroのクラフトワールド(エルダー)|muro

Sunday Preview】期間限定オーダーなやつらと - たるいのウォー

ウォーハンマー Warhammer AOS アエルフ ルミネス テクリス

ウォーハンマー ウッドエルフメイジ - 通販 - gofukuyasan.com

ヤフオク! -「ウォーハンマー アーミー」(おもちゃ、ゲーム) の落札

ウォーハンマー (ミニチュアゲーム) - Wikipedia

ウォーハンマー公式JPN on X:

商品の情報

メルカリ安心への取り組み

お金は事務局に支払われ、評価後に振り込まれます

出品者

スピード発送

この出品者は平均24時間以内に発送しています